Banned Books: Museums and Libraries Respond

In October, author Kelly Yang received notification that a parent had filed a complaint about the use of her book, Front Desk, in a school’s curriculum. The parent deemed the book propaganda, and believed the school was teaching racism by including the book in an anti-racism curriculum. Front Desk, an award-winning middle-grade novel, follows 10-year-old Mia Tang and her parents who recently immigrated to the U.S. from China.

“The purpose of school is to prepare kids for the world so they can grow up to be responsible adults and help change the world,” Yang tweeted about the challenge, including screenshots of the parent’s message. “How are they going to change it if they don’t understand what people from all walks of life are going through?”

This incident is not an anomaly. In fact, this is just one of the 300-plus attempts to remove materials and cancel services in libraries, schools and universities every year, documented by the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF). The office has been collecting censorship data since 1990 and is currently seeing an increase in attempts to censor books that raise awareness and combat racism.

Recently, a California school district removed Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes because of a parent’s complaint. The book follows a 12-year-old Black boy who is killed by a police officer and watches his community and family from beyond the grave. All American Boys by Brendan Kiely and Jason Reynolds and Monster by Walter Dean Myers were removed from a required reading list in a Tennessee middle school in order to create a “safe” and “enjoyable” environment. And in Minnesota, the largest association of public safety officers in the state requested that the book Something Happened In Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice not be recommended anymore for elementary students’ education.

OIF also continues to document attempts to remove books from collections and curriculums that contain racist language and stereotypes. LGBTQIA+ content also remains one of the most cited reasons for attempting to remove books and cancel programs in libraries.

Censorship itself is distressing, but these trends are also indicators of what society is concerned about — or in other words, what they fear. It would not be surprising if these censorship issues are reflected in literary museums.

A less-documented but prevalent form of censorship is self-censorship, when staff members themselves make a decision to not present an issue or provide materials in an attempt to avoid controversy. Both museums and libraries have the tools and resources to confront these issues. This can be in the form of hosting discussions, providing context and additional content to collections, and connecting historic issues to recent events.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House worked to inspire critical thinking using its collections. An article in the Journal of Museum Education titled “Visiting Uncle Tom’s Cabin: University-Style Discussions in a Historic House Museum” describes the successful partnership between a local retired English professor and the Harriet Beecher Stowe House that resulted in academic-style discussions hosted at the literary site. With a goal to support “creat[ing] a setting where contemporary topics of justice are discussed considering historical context,” the discussions focused on Beecher Stowe’s classic work, a book that was banned in the South due to its abolitionist message. The discussions tackled subjects such as colonization, abolition, and the term “Uncle Tom,” and examined the works of African American authors who advocated for racial justice.

The discussion series and partnership helped “avoid the pitfall of making the house a shrine to a historical figure rather than encouraging critical thinking about the person and her work,” and at the program’s conclusion, all surveyed attendees said they would recommend the series to others.

Another opportunity to spark discussions and connections to current conversations is Banned Books Week. Banned Books Week is an annual event that brings together the literary community to celebrate the freedom to read and draw attention to recent censorship attempts. It’s also an opportunity for institutions to highlight their array of perspectives in collections and affirm their defense of the freedom to read and the First Amendment.

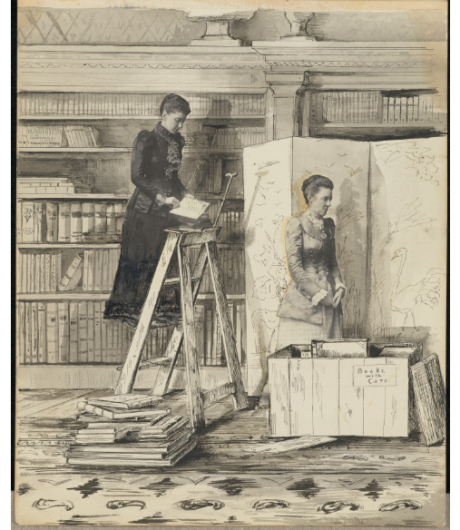

This past Banned Books Week in September marked the first time the event was celebrated mostly virtually. Many organizations focused on online and social-distanced programs. The Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library themed their events around civic engagement, hosting programs on women’s suffrage, protesting, and cancel culture. They also invited local poet Manon Voice as their “activist in residence”; during the week, Voice lived behind a wall of stacked banned books in protest of the infringement of the right to free expression.

The next Banned Books Week will take place September 26 – October 2, 2021. Lists of banned books and resources to draw attention to censorship can be explored at ala.org/bbooks. Ironically, even displays about Banned Books Week are requested to be taken down.

When specific books or programs are challenged — when a formal request has been made to remove or otherwise censor materials or services offered — libraries look to their policies. The policies outline next steps on how the complaint is handled; although specifics vary library-to-library, the target of the complaint is usually thoroughly reviewed and discussed within a board or group, which then decides whether to remove the material.

Challenges can be stressful and full of tension. By having a policy in place before complaints are lodged, museums can respond to challenges in a clear and transparent manner. Suggested language for creating these policies can be found in the American Library Association’s Selection & Reconsideration Policy Toolkit.

But responding to censorship also takes further efforts. Because censorship trends reveal what society is concerned about, confronting and discussing these complaints directly is crucial in the work to understanding and ultimately decreasing these incidents. Beyond a procedure, listening is also a critical component in responding to challenges.

“When we listen, we are offering empathy and respect,” advises OIF Assistant Director Kristin Pekoll in a Q&A with the Museum Education Roundtable. “We don’t have to agree with everything they say but by listening and treating them courtesy, we may have successfully accomplished most of what was desired: to be heard.”

While services from OIF focus on libraries and schools, museums can reach out to the office for support when censorship or controversy occurs at their institution. OIF can provide confidential communication, as well as resources and talking points.

When faced with the unknown, the world can be a scary place. But museums, libraries, and schools provide a space where readers can safely explore and learn about evolving issues. As Yang mentioned during the challenge to her book Front Desk, how are we going to change the world if we don’t know what people are going through?

Eleanor Diaz is the Program Officer at the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. With her fierce devotion to the freedom to read, Diaz organizes and publicizes ALA programs and resources about intellectual freedom, including the national Banned Books Week event. As a biblio-writer, she enjoys exploring the intersection of advocacy and literature. Diaz is also the Managing Editor of the Journal of Intellectual Freedom & Privacy.