Dime que me ves: Facilitating bilingual programs for the community

“When museums include diverse voices and perspectives, they will attract new visitors who had previously felt disconnected, intimidated, or confused. The inclusion of LatinX voices, perspectives, and opinions validates our cultural importance, creates a different mindset about culture and values, and invites different ways of seeing and understanding,” (Strategies for Engaging and Representing Latinos in Museums, 2021, p.23)

I immigrated to the United States in the middle of first grade. Despite attending a bilingual school in Mexico City, I did not communicate well in English. If I am being completely honest, I did not want to. I wanted to only speak Spanish. For me, being bilingual meant being pulled out of class in the middle of science or math for English classes; it meant being different, and not necessarily in a good way. From first to fifth grade, I was enrolled in ESL (English as a Second Language) classes which, without fail, were always facilitated by White, non-bilingual teachers who actively encouraged the erasure of my Spanish thinking and speaking. This was all done under the idea that assimilating meant acceptance and being normal. How did I cope? I watched way too much Dora the Explorer; this (somewhat) bilingual kid’s TV show until I was in middle school. Reflecting on that experience now, I realize that I was craving for someone/something to model bilingualism and biculturalism in a positive light. Although the show was not entirely in Spanish, Dora did that for me. The taste of Spanish left me feeling represented.

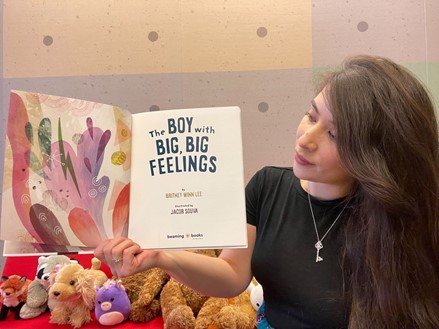

Museums are predominately White, male-oriented spaces that often lift and encourage English-speaking voices (El-Amin & Cohen, 2017, pp 8-11). When I was interviewing for my current position at the Kimbell Art Museum (KAM), the job interview included mock facilitating Pictures and Pages, a story time program for children 5 and under. When preparing, I immediately thought of my younger self. Although I was a bit older than the target age of this program when I needed bilingual programs, I thought of myself watching Dora and using the show for those 5–10 words in Spanish. From there, the idea of the bilingual story time came to fruition.

The KAM is in Fort Worth, Texas. According to the Fort Worth Government website, the racial demographics of Fort Worth are: White (Non-Hispanic): 39.4 %, Black (Non-Hispanic): 17.7%, Hispanic (All Races): 36.1%, and Other Race (Non-Hispanic): 6.8%. Additionally, according to the Fort Worth government website, the most spoken language other than English is Spanish, with most Spanish speakers coming from Mexico. Due to this, the KAM established Nuestro Kimbell in 2016. Nuestro Kimbell is a committee constructed of civic and community LatinX leaders from local organizations, such as Artes de la Rosa, the Mexican Consulate in Dallas, the Fort Worth Community Art Center, the Fort Worth Convention and Visitors Bureau, Texas Health, community advocates, local artists, and translators. These groups partner with KAM staff to strengthen ongoing programs and ensure Spanish-language inclusion throughout the museum. Additionally, the committee supports the promotion of KAM programming, building new partnerships, and developing Spanish-language resources and Spanish-language programming.

For me, representation and visibility begins with the acceptance of the Spanish language. Therefore, one of my main objectives has been the development and facilitation of bilingual programming. In my experience, bilingual facilitation historically has taken takes the following form: English learners are prioritized and then—usually at a separate and more rushed time—non-English speakers are acknowledged. This is what I experienced throughout elementary school—the interpretation that bilingualism was a disability instead of an additional ability. Therefore, when it was my turn to facilitate, I chose to not prioritize either language: English and Spanish had equal room. I wanted to tread this program as a collaboration with the community. Thinking about my friend Dora, again, she served as a bicultural and bilingual icon to me. She modeled bilingualism positively; she was not afraid or ashamed of her Spanish, instead, she taught it to the viewers. I wanted to do the same for our newly bilingual, Pictures and Pages/Fotos y Libros.

Dual language facilitation can be a tongue twister. It can become a bit confusing to say something in English and then immediately repeat it in Spanish. I find myself asking, what language did I just speak, Spanish or English? Dual language facilitation not only makes programming more accessible, but it also serves as a method for modeling. Now, Dora, is a pre-recorded program with voiceover acting. I tackle Pictures and Pages/Fotos y Libros live. Part of the facilitation and modeling is my stumbling through the balance of languages. One of the challenges I faced growing up bilingual was wanting to speak “perfect” English while maintaining my Spanish as close to perfection. Now, acknowledging that perfection is just a construct, it is important for bilingual learners to not fear slip ups or mispronunciation. Knowing two or more languages is complicated; it’s okay if it takes your brain a second to come up with words when you’re on the spot.

An additional benefit to bilingual programming is that it normalizes the inclusion of languages other than English. The more we model acceptance and diversity in terms of language inclusion, the less bilingual or multilingual learners will feel the need to assimilate into White culture. Lastly, with bilingual programming, English speakers will have the opportunity to learn Spanish alongside the Spanish speakers learning English. The goal was for this program to promote language and cultural equity while reading children’s books written by historically oppressed authors and addressing important social themes through the books, art discussion, and art making. Shortly after the debut of Pictures and Pages/Fotos y Libros, it was time for my first community collaboration with Artes de la Rosa (Artes) for their virtual month-long celebration for Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Artes has built a safe, comfortable, and courageous space for LatinX folxs to explore the arts in Fort Worth and has become an important pillar for the LatinX community in Fort Worth.

For my first collaboration with Artes, I facilitated an hour-long, virtual program on Facebook Live, consisting of a bilingual reading of Peruvian-American children’s book author and illustrator, Juana Martinez-Neal, Alma and How She Got Her Name, facilitation of three artworks from the KAM’s permanent collection (Smiling Girl Holding a Basket from the Nopiloa culture, French artist, Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Still Life with Mackerel, and Spanish painter, Luis Meléndez’s Still Life with Oranges, Jars, and Boxes of Sweets), and two artmaking activities: celebrate your heritage by creating a family recipe book and using your name as inspiration, create a watercolor painting telling the story/meaning of your name. To supplement the collaboration, the KAM supplied 100 Art Kits, filled with: construction paper, 2 sheets of plant-able seeded paper, index cards, scissors, a glue stick, a ruler, set of markers, watercolor set with a paintbrush, watercolor paper, and a white crayon, for Artes to distribute for the first 100 registrants. This program was a huge success with local audiences and even audiences from Mexico. Inspired by the bilingual facilitation, a participant even created their own video explaining their work of art in both Spanish and English.

The impact of the bilingual facilitation along with the successful collaboration was the beginning of many future partnerships. Since el Día de los Muertos 2020, we have now collaborated with Artes for Women’s History Month and Carnaval de los Niños. Upcoming, we will join forces to celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month, Día de los Muertos, and Mariachi Christmas.

There is a lot of work to continue to be done for museums to repair the harm done to historically oppressed communities. Multilingual signage, community driven committees, partnerships, and multicultural programming is a good start.

Asami Robledo-Allen Yamamoto (she/her/ella) is a disabled, Mexican immigrant who currently works at Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas as the Community Engagement Coordinator. She received her BFA in Art Education with a double minor in Psychology and Art History and MA in Art Education with a certification in Art Museum Education from the University of North Texas.

References:

El-Amin, A. & Cohen, C. (2018). Just representations: using critical pedagogy in art museums to

foster student belonging. Art Education, 71(1), 8-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2018.1389579

Aldaba, A., Espinosa, N., Munn, D. X., Sandino, M., & Reyes, S. (2021). Strategies for engaging and representing latinos in museums. American Alliance of Museums. 1-64. https://www.aam-us.org/2021/06/04/new-resource-strategies-for-engaging-and-representing-latinos-in-museums/