Social Media, Facilitation, and Rapid Response Collecting: Queer Appalachia’s Approach to Activism and Community Building

Introduction

Bryn Kelly was a good artist. Her pieces appeared in the New Museum as well as several galleries and other art institutions. Unfortunately, she was never adequately compensated for this work, which factored into financial hardship. Bryn’s situation was further compounded by being an HIV-positive transwoman. In 2016, she died from suicide. The project Queer Appalachia began as a memorial to her; it was her idea to create a zine that celebrated the intersection of homespun roots and queer identity. The project evolved into something more, an effort to help transform the world into a place she could be, one that would give people such as her more value.

Queer Appalachia – an art activism Instagram account, zine, and much more – believes that representation in art and its institutions has limited effects. It’s not enough to see oneself reflected in works of art or to have the labor from marginalized groups present. For the arts – institutional and otherwise – activist praxis needs to be incorporated. This mixture of representation and praxis is how people can best respect and support cultural workers, cultures, communities. Through this combination, the boundaries between art and activism blur, and art institutions become fully realized as tools and resources for the betterment of society. It changes from how we “consume” art to how we use it. This piece examines how Queer Appalachia combines social media, facilitation, and praxis for its audiences in order to empower them and maps how others might do the same.

Queer Appalachia

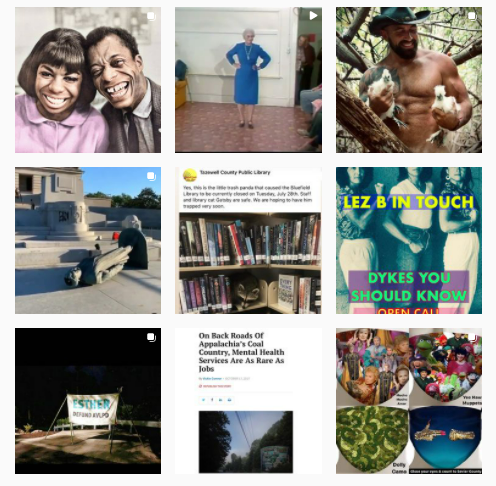

On its surface, Queer Appalachia is a social media project. It started as a zine, one that Bryn – a native of Appalachia – had spoken about doing. Once it began, Queer Appalachia received an outpour of content contributions, an Instagram account emerged, and its popularity quickly grew. As it stands, the Instagram account has approximately 268,000 followers. The project collaborated with harm reduction facilities to decrease health risks for users/sexworkers/everyone, it partnered with Atlanta’s Wussy Magazine and Southern Fried Queer Pride for online events to raise money for regional queer artists during COVID, and honestly, the list of involvement is too lengthy to cover. It also promoted regional activism and queer community by sharing events and news in its social media platforms.

Queer Appalachia transformed from its conception as a zine into an archive, community center, and hub for activism because queer people in the region asked for it. It grew to meet its community’s needs, one that consists of Appalachian and southern queers. The project thinks about its impact on younger queers in the region–how having something like this at their age would have changed access to community–and how different Bryn’s life would have been if a resource like this existed.

The launch of Queer Appalachia couldn’t have been more timely. The project started as the 2016 elections were gaining traction, while the region was being referred to as “Trump County,” and when J.D. Vance’s regionally exploitive book Hillbilly Elegy started its 70-plus-week run on the New York Times bestseller list. Queer Appalachia brought comfort and comradery to queer people in the South and Appalachians through activism, often tinged with a welcoming playfulness. It provided people with ways to get involved by highlighting activism and art.

Queer Appalachia’s Engagement and Digital Approach

Queer Appalachia lives in a digital space that enhances its mission. Because of its online nature, the project is accessible and free to everyone with access to the internet. Additionally, it is almost as easy for people to participate in the project as it is to access it. All it takes is the hashtag #QueerAppalachia to submit work. It also helped that the project created a moniker for people to connect and celebrate their identity.

The level of engagement proves to be its strongest asset and one that would benefit museum educators. Social media is often underused and/or poorly used within organizations, falling short of its potential for outreach. Museum educators can adopt aspects of Queer Appalachia to become a force of positive change within their communities. This includes finding ways to make their audiences a part of the museum–far beyond patrons or donors–by providing a space that utilizes and empowers them as artists, curators, and organizers. By seeing everyone as a contributor, museums can do more than create an interest in their institutions; they can create the next generation of artistic endeavors. In this open space, serious ideas can be explored about how to make art institutions places for change and social progress. This also requires efforts to be topical, to place art in the present while recognizing its heritage and potential future.

Because of its values and format, Queer Appalachia strives to create a sense of intimacy and immediacy with its word. Queer Appalachia manages to be both the exhibit and the infrastructure by being the space for organizing and content. In efforts to be relevant, it engages in what museums call “rapid response collecting.” In the museum world, this type of collecting involves gathering work that touches upon breaking events. Queer Appalachia does it with memes, looking to what is trending and what is pertinent to the region and queer audience. Sometimes the response indicates the project needs to be more hands-on with grants, fundraising, and events.

The role Queer Appalachia plays in archiving goes beyond rapid response collecting; it is an organization it participates in directly funding political actions within the region and documenting them. The advocacy group “Museums are Not Neutral” works to expose the myth of institutional neutrality through t-shirt and social media campaigns. The organization’s co-producers, Mike Murawski and La Tanya S. Autry, see museums as having potential to be socially engaged spaces that can create change within their communities. This idea hits close to the heart at Queer Appalachia. This is the work it does; Queer Appalachia takes a bold political stance and uses the available resources to imagine solutions. During the summer of 2020, the Black Lives Matter West Virginia chapter was created. When asked what the fledgling chapter needed, the response was funding. Queer Appalachia set in motion a t-shirt campaign, which not only paid a regional artist for a design but raised $10,000 for BLMWV in three months. While t-shirt campaigns may not be ideal or practical for museums, they have other, more powerful resources available, such as access to wealthy donors and physical space.

Providing More Than Allyship

The role of the museum needs to shift to meet the standards of new generations and to embrace activism. In short, museums should be accomplices instead of allies. Being an accomplice means working with people, not just saying you support them. It’s through this type of social partnership that they can begin to gain traction and revolutionize these institutions. Instead of positioning themselves as neutral outsiders, museums and museum professionals need to accept that these institutions are not neutral and recognize how they have an opportunity to break away from patterns of patriarchy, colonization, racism, and heteronormativity.

This change in mindset is what separates gatekeeping and curation. Gatekeepers decide what artists and cultures matter; curation thoughtfully opens people to different worlds and ways to be in them. Art becomes more than just a collection. It becomes contextualized as products or agents of events, the type that actively uplift and support oppressed communities. This is the type of world Bryn Kelly would have thrived in; it’s one that would have paid and respected minorities like her.

Our art institutes could start by making movement/activist work accessible to the public the way that Queer Appalachia does: through facilitation. These institutions need to start conversations about what makes art and its creators matter, why art is a tool for radicalizing, how communities can engage in this work together. To achieve these goals takes more than “institutional outreach.” It means the institutions have to be in a constant state of outreach in order to ensure that everyone that might need an inclusive space has one.

There is no exact formula for Queer Appalachia, though. Everyday is a slow – and sometimes clumsy – development as the project attempts to to engage with its community with integrity and compassion. Without a doubt, this results in some failures. People involved and close to the project have been participating in evolving conversations around how to moderate community dialogue and spaces, balance transparency with protecting activists, manage the recipients of emergency mutual aid funds, and what to do when campaigns don’t go as expected.

Just as institutions and museums can learn from Queer Appalachia, Queer Appalachia can and should learn from institutions. Recently, the project has found itself in a curious place. It landed on the receiving end of community critique, the type the project previously directed at regional and national nonprofit organizations. While the future and evolution of Queer Appalachia are still being figured out, the project’s impact over the years is extremely relevant. It is intended that a more resilient and transparent iteration of Queer Appalachia emerges so that the project may continue to engage in the radical and joyful work so many have connected with.

—

Chelsea Dobert-Kehn is an interdisciplinary artist and activist based in West Virginia. While working with Queer Appalachia, they organized mutual aid projects, created interactive art pieces, and lent graphic design and web development skills. During 2018-2019 they managed a gallery space at Western Carolina University’s Museum of Fine Art, where their curatorial projects addressed activism, equity, and accessibility. Their social practice art projects range from collaborating on commissions for the U.S Embassy in Niger to large scale interactive works at Burning Man.

As a Media Studies doctoral candidate at the University of Oregon, Beck Banks specializes in transgender media and transgender rurality. Originally from East Tennessee, Beck is curious about how rural-based, trans media activists understand and work within their communities. Additionally, they examine trans television representation and its purported activist efforts. Having spent years as a reporter and in higher education communication, Beck teaches several courses under the communication/media studies umbrella, ranging from public speaking to production to women and gender studies.